The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat – Summary

Table of Contents

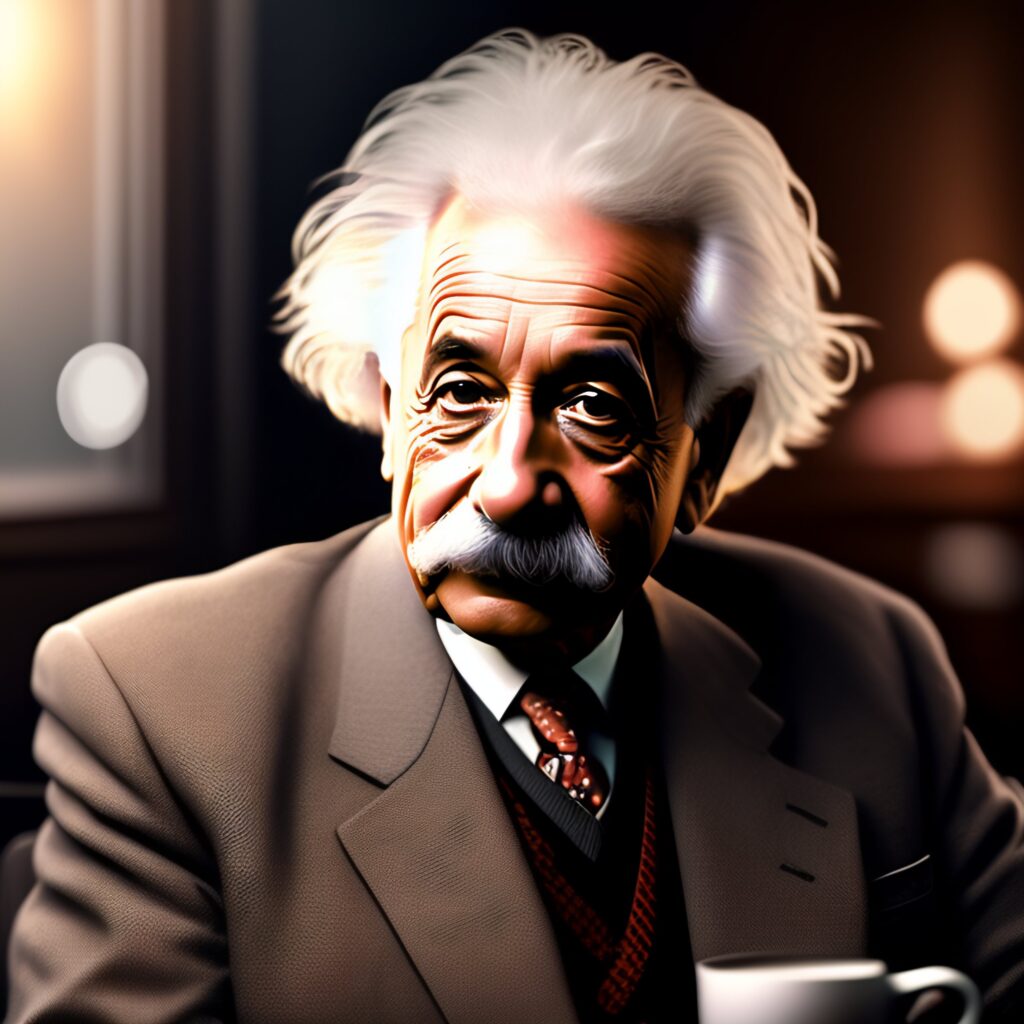

Oliver Sacks was a British neurologist, historian of science and writer who wrote one of the famous essays- The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

Dr. P. was a musician and instructor who was well-known for his extraordinary vocal and musical abilities. His inability to identify faces, including those of his students, signaled the onset of unusual issues. As a result, he frequently mistook inanimate items for living beings, which led to awkward and puzzling situations. Because of Dr. P.’s peculiar sense of humor, these occurrences were initially dismissed as jokes. But after getting diabetes, he went to an ophthalmologist, who discovered no problems with his eyes but worried about the visual portions of his brain.

Dr. P. then went to a neurologist, who noted that while his other cognitive abilities appeared to be unaffected, his interactions with the visual world were strange. He had trouble recognising people since he would concentrate on single features when facing them rather than seeing the entire face. He could play mental chess and recognise abstract shapes, but when it came to understanding faces and scenes holistically, he found it difficult.

The neurologist showed Dr. P., a portrait of his brother, but he recognised him with his physical features of square jaw, and his big teeth. Similarly he recognised Newton with his moustache. His eyes would dart all around the tiny physical features of an individual’s face.

He the carried the Platonic solids in his neurological kit but Dr. P. was able to identify cubes, dodecahedron, icosahedron, that clearly presented Abstract shapes had no problems. He then took out a pack of cards where he identified instantly the jacks, queens, kings, and the joker.

His tests then revolved around his visual memory and imagination when he found difficulties with leftness, his visual field deficits, were as much internal as external, bisecting his visual memory and imagination.

Additionally, he had trouble seeing things clearly within his head; he could recall happenings and events but not people’s faces or facial expressions. Dr. P. appeared to perform daily duties using singing. For example, he would dress, eat, and do other things while singing; if he was interrupted, he would become disoriented and forget what he was doing.

Tragically, Dr. P.’s once-skilled paintings changed from intense realism to abstract and disordered representations. The neurologist understood that the decline in his ability to depict the real world in his artwork matched the deterioration of his visual perception as a result of his severe visual agnosia, which made it difficult for him to understand the physical world.

Despite the difficulties, Dr P.’s musicality remained unaltered, and he could still perform well in his musical field. Dr. P.’s major manner of experiencing the world had changed to music, which the neurosurgeon advised him to live exclusively for. This was done to make up for his loss of visual imagery.

Dr. P.’s capacity to recognise people and the physical world deteriorated significantly as the neurodegenerative illness advanced. But Schopenhauer’s description of his relationship with music as “pure will” was true even to the end. He was unable to recognise his students by their outward appearance, but he was able to recognise them by their movements, revealing a close relationship to their body music.

The neurologist was attracted by Dr. P’s case since it demonstrated the fascinating interaction between pathology and creativity. He appeared to become more sensitive to the abstract qualities of his artwork as his visual acuity deteriorated. In the end, Dr. P’s life served as a testament to the power of music since it gave him comfort and meaning despite having serious vision loss.

Title Justification for The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

Dr. P. mistook his own wife for a hat. He caught her head considering it his hat. Rest everything can be taken from the summary about how he is diagnosed with visual agnosia due to which he had problem in recognizing and differentiating among humans. He can easily deal with non-living and abstract objects.

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat – Themes

Neurological Diversity:

“The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” clearly depicts the wide range of neurological diseases, with each offering a distinct and fascinating narrative. The book highlights the complexity of the human mind with fascinating cases like the man with visual agnosia who experiences the world in a warped, fragmented way and the person with Tourette’s syndrome whose uncontrollable behaviours interfere with daily living.

Dr. Sacks explores the various neurological landscapes, highlighting the fact that no two instances are alike. This subject emphasises the need for a complex and unique approach to comprehending and treating neurological illnesses. It exposes the difficulties faced by patients and their families and encourages a deeper understanding of the intricate workings of the brain. It raises awareness of the difficulties faced by patients and their families and encourages a deeper understanding of the complex structure of the brain. The book promotes a more compassionate and all-encompassing viewpoint towards persons who are dealing with these disorders by highlighting the variety of neurological variation.

Identity and Self-Perception:

“The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” examines situations where identity and self-perception are distorted by neurological illnesses. The extraordinarily affecting accounts of patients who find it difficult to identify their own bodies, faces, or loved ones raise existential queries about consciousness and self-awareness. In his exploration of how the brain creates our sense of self, Dr. Sacks navigates the tricky terrain of identity.

The reader is encouraged to reflect on the fundamental nature of existence as well as the complex interactions between the brain and what it means to be a human. It questions prevailing ideas of selfhood and cultivates an understanding of the vulnerability of identity in the face of neurological disorders. The subject invites philosophical reflections on the essential elements of human identity and how we view ourselves in the absence of a cogent physiological explanation.

Intersections of Art and Science:

explores examples where neurological disorders and artistic expression coexist, offering a light on the complex connection between the brain and creativity. In his case studies, Dr. Sacks describes individuals who have neurological conditions who also exhibit amazing artistic abilities.

Readers are prompted to consider the neurobiological bases of artistic ability and the possibility that neurological disorders may open up hitherto untapped creative vistas by considering this issue. It stimulates a greater understanding of the arts’ role as a window into the complexity of the human brain. By demonstrating how art and science interact, the book promotes interdisciplinary research and piques readers’ interest in the relationships between imagination, creativity, and the complex processes of the brain.

Empathy and Compassion:

Dr. Sacks exhibits an extraordinary degree of compassion and empathy in his contacts with patients throughout the whole book. He presents these people as real people with rich emotional lives and distinctive life experiences rather than just medical cases. This subject emphasises the significance of treating patients with neurological illnesses with respect and understanding, promoting a closer relationship between medical professionals and individuals who are receiving their care.

In order to debunk myths and stigmas associated with neurological illnesses, the book invites readers to develop empathy for people who are dealing with neurological issues. It urges society to adopt compassion as a guiding principle in assisting people with neurological diseases by serving as a poignant reminder of the importance of empathy to delivering holistic and humane healthcare.

Read more: the-school-in-the-forest